This is American ginseng. Well, that’s not its real name—the real name is Panax.

Native to eastern North America, this humble plant quietly thrived in the wild for centuries. However, in 1720, its story changed forever. Little did it know that across the Pacific Ocean, it would become a highly sought-after panacea by people it had never encountered. This is a story of how far placebos can go.

Chinese people take great pride in their traditional medicine. Yet, if you know anything about Chinese medicine, you should also know it’s full of crap—literally. Many so-called remedies are made from animal and even human feces, cleverly disguised with poetic names to make them sound sophisticated. For example, 夜明砂, meaning "night-shining sand," is used to treat night blindness. What is it actually? Bat feces—because, you know, bats can see at night. Another example is 金汁, or "golden potion," which is young boys’ feces mixed with water and buried underground for two to three decades. It was believed to treat fever. You get the picture.

Instead of using modern scientific methods to assess their practices, Chinese medicine practitioners often cling to ancient texts written by people who had no knowledge of chemistry or biology. They believe their ancestors had already unlocked the mysteries of human health. Trapped in a time capsule, they scour old books in search of secret formulas, as if medicine were alchemy rather than science.

One major theory in Chinese medicine is the five elements system, which assigns each organ to an element: the heart to fire, the lungs to metal, the liver to wood, the kidneys to water, and the stomach to earth. Another widely accepted principle is 以形补形. The idea is simple: if you want to strengthen a body part, eat something that looks like it. When I was a kid I want to dunk, people told me eating frog legs would help me jump higher. And for all the men out there eating animal genitals and testicles—we all know what you’re hoping for.

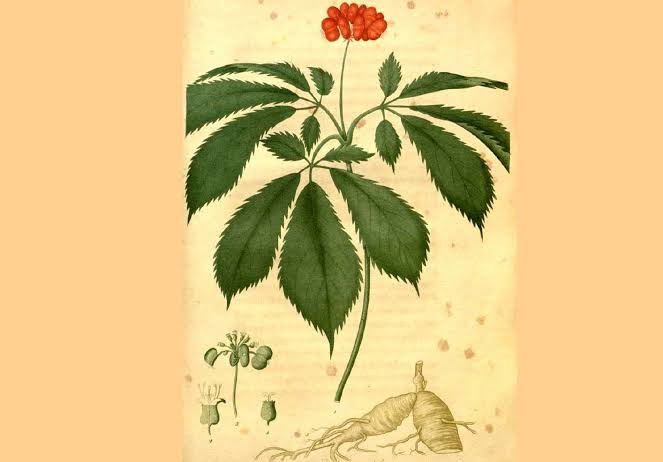

Chinese medicine does contain many great herbs, and if there is a tier list, ginseng would be firmly in the S+ tier. Ginseng is the root of a plant, and because it vaguely resembles a human figure (if you squint hard enough), people believed it to be the ultimate cure-all. What could be better for the human body than consuming a plant shaped like one? Remember, 以形补形.

To reinforce this belief, people crafted elaborate legends about ginseng. Some say wild ginseng can run away, which is why people tie red strings to it. Others tell of thousand-year-old ginseng roots transforming into a human baby with magical powers. Those who consume it claim it cures nearly everything—regulating blood sugar, improving memory and circulation, lowering cholesterol, boosting the immune system, reducing stress, increasing energy, and even treating erectile dysfunction, you name it. It is said to grant immortality. Even if you die, a thousand-year-old ginseng might bring you back to life—like a video game power-up that grants you an extra life.

But let’s be real: traditional Chinese medicine has no concept of an immune system, blood sugar, or cholesterol. Most of its claimed benefits are vague at best. Remember when I talked about Qi in another article? Yeah, ginseng is supposedly good for your Qi—or your chakra, if you’re into that. Neither exists.

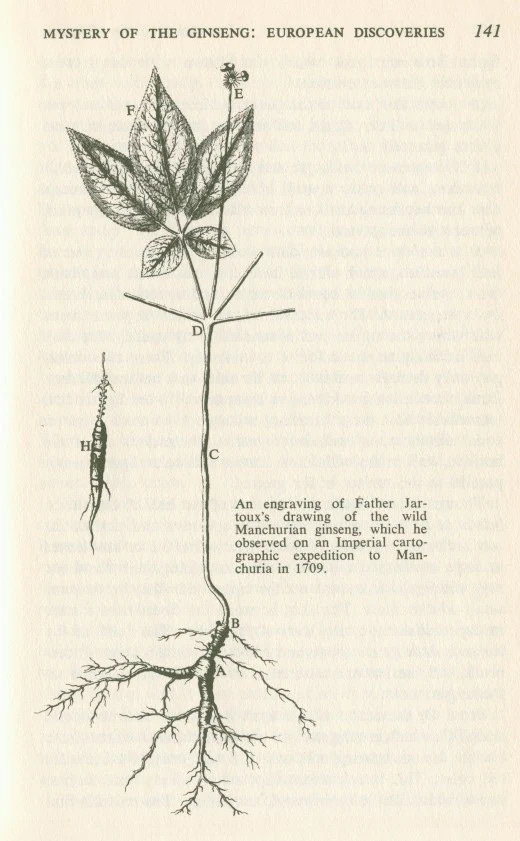

Now, how does American ginseng fit into this story? Well, because ginseng was so rare and valuable in China, demand skyrocketed. After years of overharvesting, wild ginseng nearly went extinct. Only the wealthy and royal families could afford it. In 1701, a French Jesuit named Father Jartoux, who was in China, witnessed the ginseng craze and published an article introducing it to the Western world. He suspected that similar plants might be found in regions with climates like northeastern China. Another French Jesuit, Father Lafitau, read the article in Montreal and thought, "Hey, Montreal’s climate is similar." With the help of Native Americans, he found American ginseng in 1716.

Imagine stumbling upon an ordinary plant in your backyard that no one cares about, only to discover that it sells for an outrageous price in another country. Since 1720, billions of American ginseng plants have been harvested and exported to China. By the end of the 19th century, it was nearly extinct in Canada. The situation became so dire that the government had to step in to protect it. As business boomed, Western entrepreneurs turned to the U.S., where they found abundant ginseng in the Appalachian Mountains. To this day, the bestselling ginseng in China is marketed as "Wisconsin ginseng." In fact, the name of American ginseng in Chinese is 西洋参,it literally means ginseng from western countries. Another name is 花旗参,it means ginseng from the country with colorful flag aka American flag. Like gold rush, many flooded in the mountains to harvest these plants and made millions.

American ginseng’s conservation status is now globally vulnerable. It is imperiled or critically imperiled in 14 states and provinces, and in Canada, it is endangered and facing imminent extinction. Fortunately, most American ginseng sold today is cultivated rather than wild-harvested.

So, the question has to be asked. Is ginseng really that effective? That’s a question you’ll never get a clear answer to—one that sparks endless debates. On one side, Chinese people fiercely defend their traditions with countless miracle stories and limited data. On the other, critics argue that many studies on American ginseng suffer from small sample sizes, inconsistent methodologies, and industry bias. Some researchers suggest that the supposed benefits stem largely from the placebo effect—especially in traditional Chinese medicine contexts where belief in ginseng’s healing power plays a significant role in patient perception.

Here’s my two cents. First, this stuff tastes awful. I’m not exaggerating—it’s intensely bitter and earthy in the worst way. Second, the active ingredient, ginsenoside, is present in the stems and leaves at concentrations of 3–6%, compared to just 1–3% in the root (which is what people actually eat). So if it’s effective, why not consume the leaves or stems instead? Most importantly, if ginseng is truly that miraculous, why is it only popular among Chinese and Koreans? Some Native American tribes have used it for herbal remedies, but modern science still can’t validate its supposed benefits.

Don’t get me wrong—modern science is far from infallible. It has been wrong countless times, particularly when it comes to medicine and supplements. But Chinese medicine is on a whole other level. The ginseng trade is now almost a billion-dollar industry, with over 90% of American ginseng exports going to East Asia. Think about it—if it were so valuable, why wouldn’t Western countries keep it for themselves instead of selling it off like cheap trinkets?

Speaking of overpriced placebos, another supplement beloved by the Chinese is sea cucumber. In Chinese, it’s called 海参—"sea ginseng." It’s the same story all over again. Another billion-dollar industry, another "miraculous" supplement with extravagant health claims that modern science refuses to endorse, and another product that only the Chinese seem willing to splurge on.

Sometimes, I can’t help but marvel at the absurdity of it all. When money and tradition are involved, some will gatekeep the truth while others buy into the illusion—amusing themselves with nothing more than an expensive placebo.