The History of Brain Rot

A term coined 170 years ago

In 1854, American writer Henry David Thoreau described his two years, two months, and two days living in a regenerated forest by Walden Pond in his famous essay collection Walden. At that time, the Industrial Revolution in the U.S. was in full swing. Though Thoreau lived a secluded life away from the clamor of society, he keenly observed that technological progress was leading to a widespread intellectual and cognitive decline. In the book’s remarkably argumentative conclusion, Thoreau repeatedly pointed out this dangerous affliction—people tended to devalue complex or multi-interpretative thoughts, favoring instead simple ideas. He wrote:

“It appears as if nature can only sustain one order of understanding… as if there were safety in stupidity alone.”

“I desire to speak somewhere without bounds; like a man in a waking moment, to men in their waking moments”

Building up to his argument, Thoreau delivered a quintessentially Thoreauvian rhetorical question:

“While England endeavors to cure the potato-rot, will not any endeavor to cure the brain-rot, which prevails so much more widely and fatally?”

Here, Thoreau linked the words brain and rot with a hyphen, creating the new term brain-rot to parallel the disease that decayed potatoes. What’s remarkable is that unlike many newly coined terms that fade away quickly, brain-rot has persisted for the past 170 years. One could argue that the history of brain-rot is also a history of media evolution, technological iterations, and the reflections they have provoked. From the perspective of reading culture, it represents the gradual decline of deep reading. This phenomenon has become even more apparent in the algorithm-driven era of social media, where an endless stream of low-quality, short-form content, along with the addictive loop of smartphones, algorithms, and dopamine, has thrust brain-rot into the global spotlight once again.

To understand this, we must go back to the time of Thoreau’s birth in 1817. Back then, the world was still dominated by print. America’s mainstream media consisted of printed words—primarily newspapers and books. British immigrants to North America mostly came from educated backgrounds and had strong reading habits. Upon arriving in America, they established libraries and schools. Trade with Britain brought a wealth of books—covering art, science, and literature—which met the intellectual demands of the population. One crucial consequence of this was the emergence of a vibrant reading culture that transcended class, unlike Britain, where literary culture was monopolized by the elite.

In the early 19th century, the number of libraries in the U.S. skyrocketed. Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851) sold over 300,000 copies in its first year, despite the U.S. population being only about 70 million at the time. Americans also loved public lectures, leading to the widespread popularity of lecture halls. Influenced by the dominance of print, speakers often used formal language and complex sentences, addressing serious topics in lengthy talks that could last for hours. Yet audiences remained highly engaged, equipped with knowledge of history and intricate political matters, and capable of understanding complex sentences. If a speech was particularly compelling, they would spontaneously applaud. As a young civilization, America was more obsessed with print and print-based oratory than any other society.

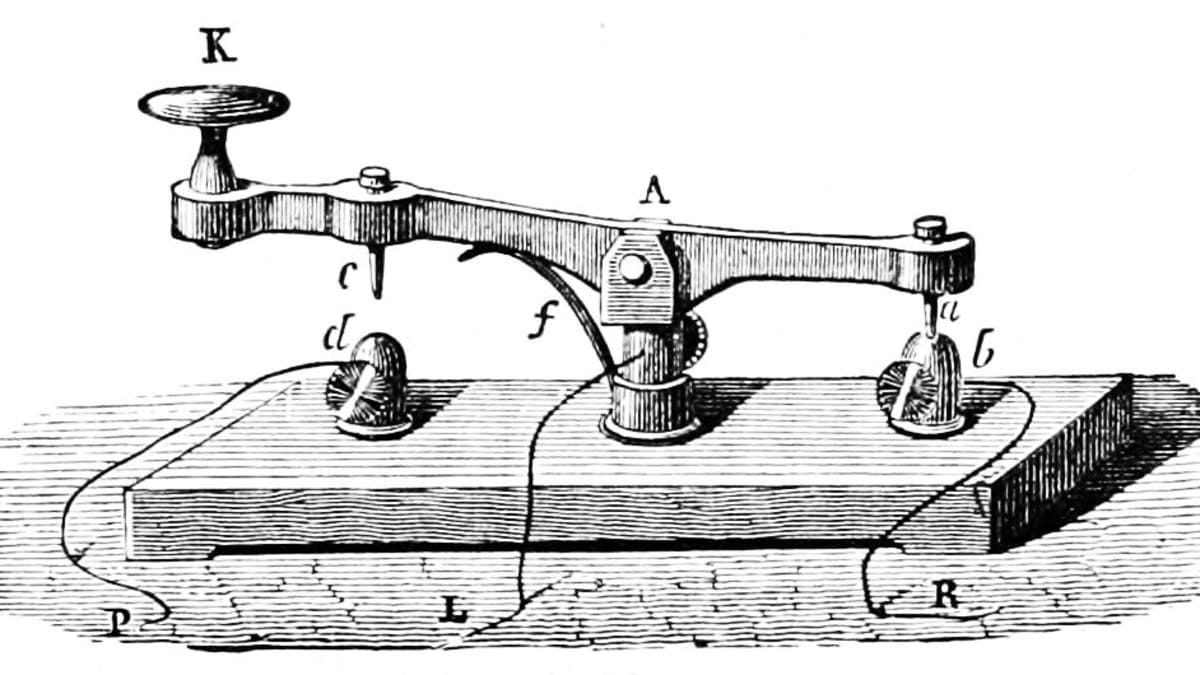

However, all of this was soon destabilized by the invention of the telegraph in 1837. The emergence of this technology effectively divided human civilization into two eras. Before the telegraph, the speed of information transmission was the speed of a carriage, a ship, or a train—roughly 60 km per hour. This relative slowness allowed time for reading, thinking, filtering information, and making informed decisions. The telegraph, however, erased these boundaries, collapsing distances and integrating everyone into a single information network. Suddenly, people could learn about major events happening thousands of miles away and send messages of safety and longing to distant family members. Yet, the telegraph also shifted newspapers’ priorities—no longer was their success determined by the quality or usefulness of news, but rather by the remoteness of its source and the speed at which it was obtained. Thoreau was one of the first to perceive the information overload this new technology brought:

“We have built a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas, but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate… We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the old and new worlds together, but perhaps the first news that will reach American ears will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough.”

The invention of the telegraph transformed America into a single “community” and permanently altered the nature of newspapers. Local news and timeless topics were displaced by war reports, crime, traffic accidents, fires, and floods. The defining traits of these news stories were sensational headlines, fragmented structures, and incoherent language, with no specific target audience. These stories, structured like slogans, were easy to remember and just as easy to forget. Often, one news piece had no logical connection to the next. Increasingly, people began to notice the brain-rot effect of newspapers—readers consumed a massive volume of information yet seemed to retain nothing of substance. The root cause was the telegraph’s fragmentation of information into disconnected symbols, tearing apart people’s time and attention.

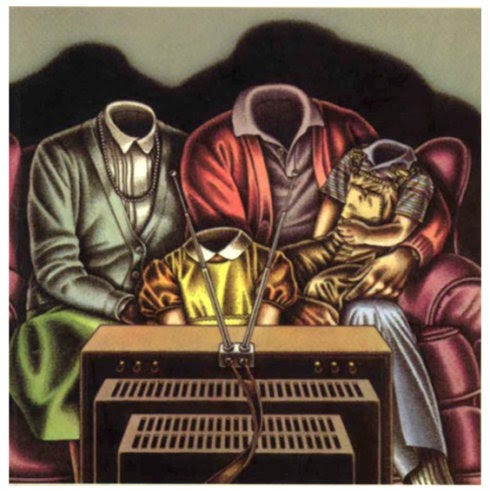

If the telegraph planted the seeds of shallowness in reading culture, then the advent of television in the early 20th century sought to uproot it entirely. Unlike print, television did not simply extend the written word—it fundamentally replaced reading with watching, making visual entertainment the basis of judgment. Some might ask, Can’t television also foster deep thinking? The answer is: almost never. The average shot in television lasts only 3.5 seconds, leaving no time for the eyes to rest. The screen constantly injects new stimuli into the brain. More importantly, television’s core appeal is visual excitement, making it an art of performance rather than thought.

This nature of television—its need to satisfy visual pleasure—is precisely why entertainment flourished. Humanity has always needed entertainment, and this in itself is not a problem. However, the brain-rot obsession with television had an unforeseen consequence: it transformed politics, religion, business, education, law, and all critical aspects of society into forms of entertainment, leaving little room for thought. In the end, people looked around in shock to find that whether on their screens or in their daily lives, only one voice remained—the voice of entertainment.

Unlike reading, which is an autonomous, self-directed activity that allows for pauses and reflection, television forces viewers into a passive state, bombarding them with a relentless stream of visual information. What captures attention is not knowledge, thought, or emotion, but sensory stimulation. Worse yet, a heart-wrenching news report might be immediately followed by a celebrity gossip segment, leaving the mind blank and emotions chaotic.

Ultimately, while both books and television are human creations, they are fundamentally different mediums. In fact, all tools and media reshape, influence, and even enslave the human mind. As Nietzsche keenly observed in 1867:

“My thoughts on music and language are often shaped by the quality of the paper and pen I use… The tools we use participate in the formation of our thoughts.”

In 1884, American psychologist William James proposed a revolutionary hypothesis: "The nervous system appears to be endowed with extraordinary plasticity... Over time, both external and internal forces can cause that structure to become different from before." This idea was as explosive as British biologist Darwin's announcement that humans evolved from apes. It wasn't until 1968 that this brilliant conjecture was fully confirmed by neuroscientist Merzenich's groundbreaking work. In this profound experiment, Merzenich first severed certain nerves in monkeys' hands and found that their brains initially became chaotic; but after a few days, he was amazed to discover that the monkeys' brains had reorganized themselves, with neural pathways weaving into a new map that aligned with the new nerve arrangement in the monkeys' hands. Thus, the secret that Nietzsche vaguely sensed a hundred years earlier was finally revealed: technology, media, and tools can reshape our brains and thinking—from books to newspapers to television, each technological and media revolution has triggered concerns and discussions about "dumbing down" (which is another expression for "brain rot").

In fact, when Plato wrote down his philosophical masterpieces with a pen (his teacher Socrates only believed in memory and dialogue, refusing to write), when Nietzsche wrote using a spherical typewriter, when people in the short video era complained that they could no longer read any long texts, they were all touching on this central theme in human civilization. How we discover, store, and interpret information, how we direct attention, how we mobilize our senses, how we remember, how we forget—all are influenced by technology, media, and tools. The use of technology, media, and tools strengthens some neural circuits while gradually weakening others, making certain mental characteristics increasingly prominent while causing others to disappear. On the surface, we are using and manipulating tools; in reality, tools are shaping each of us.

In the latter half of the 20th century, more and more insightful people recognized the negative impact of television culture, especially Professor Neil Postman, whose 1985 book "Amusing Ourselves to Death" incisively analyzed the mental disaster caused by television culture and had a widespread global influence. However, at the end of the book, Postman gave a pessimistic conclusion: it is impossible for people to simply give up television. He cited an example: in 1984, a library in Connecticut advocated a "Turn Off the TV" campaign—the theme was to encourage people not to watch television for a month. However, television media widely reported on this activity, and it was hard to imagine that the organizers didn't see the irony in their position. Postman himself felt the same way, writing: "Many times, people have asked me to go on television to promote my book about opposing television, which is equally ironic. This is the contradiction of television culture."

Neil Postman passed away in 2003. In the twenty years since, the entire world has undergone earth-shattering changes again. If Professor Postman were alive today, he would certainly be amazed at how social networks have almost redefined the media culture he spoke of. Today, the younger generation is no longer addicted to television culture like people in the past; they have something more attractive—social media. In 2023, mobile internet users averaged 435 minutes of screen time per day, approaching the ideal sleep duration. People have become accustomed to switching between various platforms daily, browsing news, watching short videos, ordering food, shopping, interacting, and liking posts. Each platform has different functions and content focuses, and as users swipe with their fingertips, they also switch between different roles they play. However, there is too much low-quality and even garbage content online, with fabricated short video scripts frequently harvesting emotions, and algorithms exacerbating biased "information cocoons." The more people scroll on their phones, the more spiritually hollow they seem to become, and it is precisely because of this spiritual emptiness that dependency on phones increases. Perhaps this is truly a disease.

On December 2, 2024, "brain rot" was selected as Oxford Dictionary's Word of the Year for 2024, bringing renewed global attention and discussion to this term created by Thoreau 170 years ago. According to the official explanation from Oxford University Press, "brain rot" refers to a perceived deterioration in a person's mental or intellectual state, describing the negative mental impact caused by excessive browsing of low-quality content online (especially on social media). Oxford Dictionary Chairman Casper Grathwohl stated that the term "brain rot" reveals the potential risks of virtual life and how we use our leisure time, which seems to mark a new chapter in the collision between humanitarian concerns and technological development.

Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari pointed out in his new book "Nexus" that algorithms have discovered that hate-filled conspiracy theories better increase human engagement on social platforms. So, algorithms made a fatal decision: spread anger, spread conspiracy theories. And these discussions based on anger and conspiracy theories are actually the most meaningless, the least likely to reach consensus, and the least helpful in promoting social progress. From this perspective, those contemporary "brain rot" devices, while completely meaningless, occupy the eye of the cyber storm due to the provocation of low-level emotions, algorithmic recommendations, and self-emotional projection. After more than 20 years of rapid internet development, we seem to be gradually reaching a consensus about the ugly cyber world. As the flood of information surges forward, our brains have become offerings sacrificed to the "cult of traffic worship."

However, technological iteration never has an endpoint. The current rising AI wave is gradually penetrating various aspects of life, "silently" changing the landscape of the future world. In fact, the nominated word "slop" has to some extent already demonstrated AI's enormous impact on society. According to the official explanation, "slop" refers to AI-generated art, writing, or other content that is casually or massively shared and distributed online, usually low in quality, lacking authenticity or accuracy. In this era of intelligence explosion, the gap between the information people encounter, the information they absorb, and the information they truly need is constantly widening. How can ordinary people extract nourishment from this "ocean of information" on the internet and reject "brain rot"? Returning to the "primitive era" is unrealistic; we must learn to coexist with messy information and maintain our ability to think independently, especially to think deeply. Of course, appropriate "digital detox" and intentional blank spaces in life can be remedies for self-healing, as Cal Newport states in "Digital Minimalism":

(Digital minimalism is) a philosophy of technology use that concentrates your online time on a small number of carefully selected activities that strongly support things you value, and then happily miss out on everything else.